In this post we take a detailed look at why you should train your adductors for both rehab and sports performance. We also look at the reasons why the adductors seem to be so undervalued in both.

At a glance

The adductors are often overlooked, but they play a critical role in stability, movement efficiency, and injury prevention.

They’re not just “groin muscles” — adductors help control hip motion, contribute to pelvic stability, and assist in nearly every lower body movement.

Weak or underused adductors are linked to common issues like groin strains, hamstring problems, and knee pain.

They work dynamically and isometrically in many sports — especially in change of direction, deceleration, and lateral movement.

Effective adductor training includes resisted hip adduction.

Training should focus on control and progressive loading, especially in end-range positions.

Better adductor strength = improved performance and reduced risk of injury in both rehab and athletic contexts.

Introduction

In rehab and exercise more generally, there tends to be a bias towards stretching some muscles and strengthening others.

These are usually the same muscles for everybody.

We’re encouraged to stretch our chest muscles and strengthen our back muscles for example, or stretch our hamstrings and strengthen our glutes.

These simplistic, protocol driven approaches are usually based on postural assessments, or what we tend to do for most of the day (sit in front of a computer).

Not only is this paint by numbers approach misleading, it also results in some muscles being ignored.

One such group of muscles is the adductors.

Adductor anatomy

A good indication how important a group of muscles may be is their size and number.

Pop your hand on the inside of your thigh near the top of your leg and grab a handful of tissue. That entire bulk is made up of your adductors.

They include:

Pectineus.

Adductor brevis.

Adductor longus.

Gracillis.

Adductor magnus.

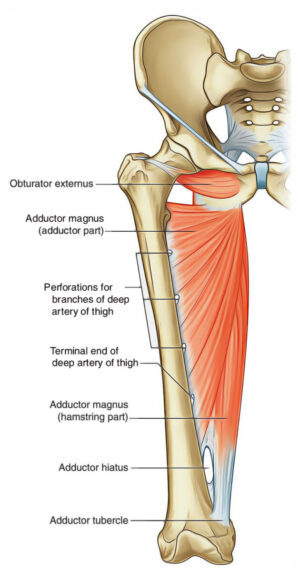

The most fascinating of them all has to be adductor magnus. This triangular shaped muscle is the second largest in the lower body after Glute Max.

It fans out from its origin on the bottom of the pelvis (the pubis and the tuberosity of the ischium), to insert on the inside of the femur and on the adductor tubercle close to the knee.

Adductor magnus functions as two distinct muscles. It has an adductor portion and what is commonly called a hamstring portion.

As a result it’s capable of adducting your hip (bringing one leg towards the other), flexing your hip, extending your hip and both internally and externally rotating it.

It contains four small tendinous arches close to its attachments on the femur, through which branches of the profunda femoral artery pass.

To top that, it also contains a large hole nearest the knee called the adductor hiatus. This allows both the femoral artery and the femoral vein to pass directly through the muscle on their way to the popliteal fossa behind the knee.

I promise I’m not making this stuff up.

Adductor function

As their names suggest, all of the adductors will bring your thigh from an abducted position (leg out to the side) back towards your other leg.

With the exception of the so called hamstring fibres of adductor magnus, all will flex your hip from a neutral position. The majority produce internal hip rotation, whilst adductor longus is also capable of producing external rotation.

Because of their attachments on the bottom of the pelvis, they also have an influence on pelvic stability.

Why your adductors are important

So that’s cool but what does it all mean in terms of function?

It’s probably not difficult to see how your adductors would be important for sports that require you to return from side lunging positions such as tennis, squash or badminton.

And for sports that require rapid acceleration, deceleration and change of direction like football, rugby, or hockey.

They’re also crucial for activities like golf and baseball which require significant hip rotation.

The adductors are not just important for sport however

I’ve written before how critical hip flexion is to our daily lives. You wouldn’t be able to walk, run, or move up stairs without it. Your adductors are significant contributors to this motion.

The majority also produce internal rotation of the hip, which is an important component of pronation. This is a series of joint motions that enables you to absorb forces from activities like walking, running and jumping.

In addition the adductors provide a counterbalance to the powerful hip extensors. Without flexion and internal rotation of your hip, you wouldn’t be able to adequately lengthen and load your glutes.

Interestingly a recent study found the adductors grow at a similar rate to both the quadriceps and glutes when loaded in a squat exercise. More so from a deep squat position, where the majority of them become hip extensors.

Why the adductors are thought of as tight and in need of stretching

This is partly due to research on knee injuries and flawed assessments such as the single leg squat.

Some studies have found an association between increased hip adduction angles during walking and running and the existence of a variety of knee injuries. These include iliotibial band friction syndrome (ITBS), patellofemoral pain syndrome (PFPS) and osteoarthritis of the medial compartment of the knee.

Whilst most of the research has focused on training the abductors to control this motion, it seems some coaches, trainers and therapists have made the leap that stretching the adductors will also help.

There is no evidence that this approach has any effect on these issues.

The single leg squat assessment

The single leg squat is still used as a movement screening tool to assess stability and control of the hip and pelvis in a single leg stance.

If your knee dives inwards during the test, the response of the examiner is usually to diagnose weak hip abductor muscles and tight adductor muscles.

As this video explains however, that probably occurs because your brain is attempting to maintain your centre of mass over your base of support, rather than being indicative of tight or weak anything.

Performing a single leg squat doesn’t really tell you why any particular movement is occurring. It just tells you it is.

Gait analysis

Likewise analysing somebody’s walking or running gait can be equally misleading.

Take a look at this video of a client who was complaining of left hip discomfort whilst walking as an example.

Subjectively his left foot appears to be toeing in a little as he walks and he seems more unstable on his left side.

On the treatment table he had a large limit in left hip internal hip rotation.

There is nothing in how he was walking to suggest this might be the case. If anything the position of his foot would suggest an external hip rotation limit.

I filmed him walking again after restoring his left internal hip rotation. Again this is subjective, but his left foot is no longer toeing in and his gait looks more fluid. He reported feeling more stable through his left side.

Whilst this proves little, what it demonstrates is how difficult and misleading assessing a multi joint task such as walking or running can be.

Diagnosing a muscle group as tight simply because a joint is moving in a particular direction is inaccurate and unreliable.

So should you train your adductors?

I’m sure you know what I’m going to say if you’ve read this far.

Training a muscle group the size of your adductors will provide enormous value.

Whether you want to improve your sports performance, your squat, reduce your risk of groin injuries, keep your knees healthy and pain free, or just move better, focussing on improving the strength of your adductors will help.

Below I discuss both home training and gym based options.

Home exercises to train your adductors

We know the adductors are all involved in adduction of the hip. If you want to challenge them this is one of the most effective motions to load.

You can do this at home by attaching a band around your lower leg and placing a slider under your heel to reduce the friction of the moving leg.

In the image above I’m also using a kettlebell to brace my other leg.

Keep your pelvis level throughout and don’t let the band take your working leg further out to the side than you can take it by yourself. Measure this before you start to be sure.

The band should form a 90 degree angle with your working leg when it’s in the abducted position (out to the side).

Gym based exercises to train your adductors

If you’re lucky enough to have a hip adductor machine in your gym then this is a great option to strengthen your adductors.

I’ve written before that these machines are the most misunderstood in any gym. My male clients often joke they’re the only men using them. That tells you everything you need to know about the state of education in the fitness industry.

Better machines will allow you to alter the position of the back rest which changes the hip flexion angle you’re working in.

The is useful because it enables you to train your adductors in the position they most frequently work when you run or walk.

If the machines in your gym don’t have that capability, use a couple of yoga blocks to bolster the seat. This will reduce your hip flexion angle a little and provide a different stimulus.

The biggest mistake people make when setting these machines up is to force their hips passed there active range of hip abduction. This is usually done by raising themselves off the seat and cranking the pads out to the side. Don’t do this.

As with any exercise, having an external resistance take you into a position you don’t have muscular control of can lead to issues.

Summary

The adductors are certainly the most undervalued muscles of the lower body in both rehab and sports performance.

Training them will improve your performance in many different activities and help you both recover from injury and avoid it in the first place.