In this post we discuss why you can have pain without injury and the other factors involved in creating the pain experience.

At a glance

Scans typically reveal structural changes even in people without pain, highlighting that imaging doesn’t reliably predict discomfort.

Pain can vary daily—you might bend over one day without issue, and struggle the next—even if nothing structural has changed in your body.

It can also be triggered by sensory disturbances, such as the brain receiving feedback that it didn’t expect.

Pain is multifactorial. It’s influenced by your nervous system, emotional state, your environment, sleep, stress, and nutrition—not just structure.

Focus on updating how your brain processes movement through intelligent training, stress management, and lifestyle.

Introduction

We all experience unpleasant sensations in our bodies from time to time. A back that aches for example, or a sore knee.

Sometimes these sensations seem out of the ordinary however, or sometimes they stick around longer than we would like.

This might motivate us to investigate further.

Usually this begins with a visit to the doctor. Once anything serious is ruled out you may be referred to a physiotherapist.

If the issue persists, imaging of the relevant area might be suggested to see if anything structural is responsible.

Scans don’t show pain

A scan will usually show something.

Scan anybody and you will find structural changes. These are a normal part of the ageing process.

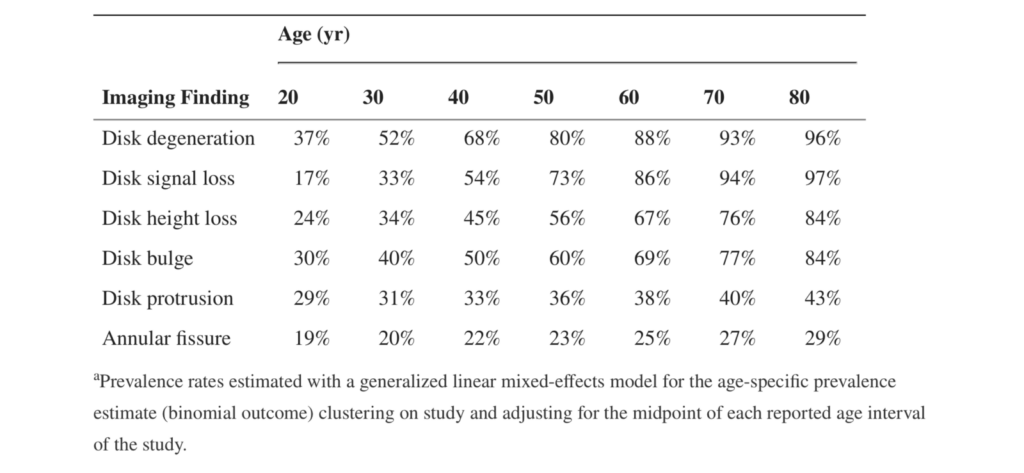

The following table shows how prevalent changes in the spine are for example. Crucially none of these individuals had back pain.

Different behaviour of pain

Despite our desire to neatly diagnose and categorise structural changes, it’s clear that pain doesn’t behave in this way.

The connection between what you feel and whatever structural issue you may have been diagnosed with, isn’t simple. This is particularly true if the issue has been around for a while.

For example, if you have a back issue, you may have noticed that sometimes you can bend over without pain. Other times this causes a problem.

If you suffer with knee pain, you might find that some days you can walk for miles, other days getting to the end of the road is a challenge.

Why the difference?

Pain can be induced without injury

To complicate the matter further, pain can be induced by simply creating a disturbance in your body’s feedback mechanisms.

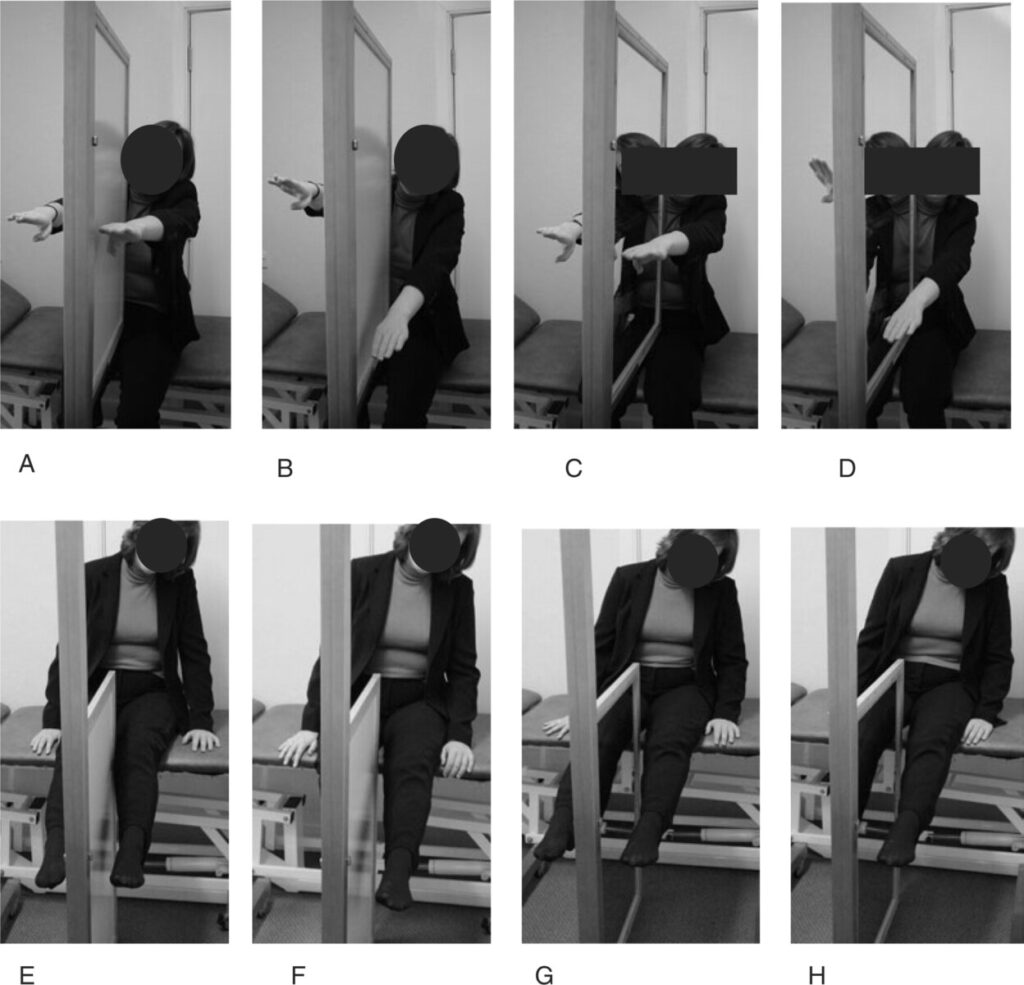

In this study subjects sat with one limb (either their arm or leg) obscured by either a large white board or a mirror.

They were then asked to either move their limbs together, or hold one still and move the other. All while only being able to view one side of their body.

When the subjects were viewing their moving limb in a mirror, whilst holding the obscured limb stationary, many experienced unpleasant sensations.

These ranged from temperature changes in the obscured limb, right through to tingling and shooting pains.

This was thought to be due to the difference in what the subjects were seeing (a reflection of their moving limb) and what their central nervous systems were detecting (a stationary limb).

So if your central nervous system is capable of producing pain when it detects aberrations in feedback, you can probably see how it can produce pain when there’s no injury present.

Pain is multifactorial

Pain can be thought of as an alarm. It’s your built in warning system.

Unlike a standard alarm, it can be tempered or ramped up by the general state of you, the organism.

In 1977 George Engel proposed that humans were not merely biological systems and that our health could be impacted by both psychological and social factors. This became known as the biopsychosocial model.

There’s plenty of evidence to substantiate this model. We know that people under psychological stress will fair worse with disease. Likewise loneliness has been shown to have the same effect on health as smoking 15 cigarettes a day.

Despite this, many medical practitioners still heavily weight the bio part of the biopsychosocial equation.

Think about your own experience, whilst you were no doubt given exercises to help improve your situation, how useful is this if you’re sleeping less than 6 hours a night and making poor food choices?

Summary

Pain is multifactorial. Chasing it by focussing solely on structure and mechanics addresses only one part of a bigger picture.

In the absence of recent injury or disease, think of pain as an indication to make broader lifestyle changes.