In this post we discuss the best exercise for knee Osteoarthritis and dispel some common myths about the condition.

At a glance

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a disease of the whole joint (not just cartilage) and is driven by systemic inflammation.

Exercise helps—but must be within your joint’s tolerance (avoid too much too soon).

Strength training is the most effective intervention:

- Builds stronger muscles.

- Reduces pain and improves function.

- Can be done with moderate loads, not just heavy weights.

Joint forces matter:

- Choose activities carefully and listen to your joints.

- Running may be fine for some, problematic for others.

- Golf and other activities can still stress the knees—adjust duration or intensity if flare-ups occur.

Biomechanics influence OA progression:

- Knee alignment (varus/valgus) shifts OA risk to different compartments.

- Strengthening hip and ankle muscles can help redistribute forces.

Body fat worsens OA through systemic inflammation.

Key recommendations:

- Prioritize resistance training (especially knees, hips, ankles).

- Add endurance activities (walking, cycling).

- Manage body weight to reduce inflammation.

What is Osteoarthritis (OA)?

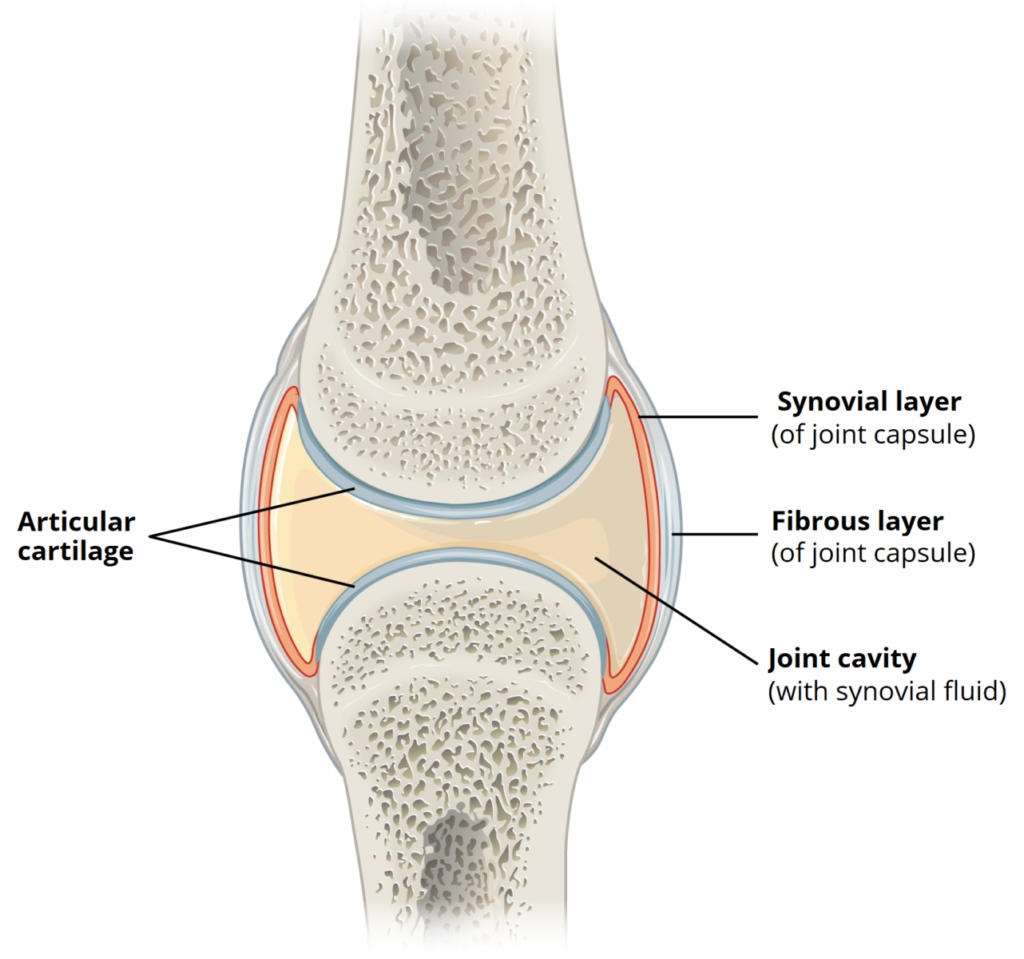

OA is a disease that impacts the cartilage which covers the ends of bones and allows frictionless movement of your joints.

It also has an effect on the subchondral bone immediately underneath the cartilage and the lining of the joint capsule. It’s more accurate to say OA is a disease of the joint rather than just the cartilage.

The cause of OA is complex. It used to be considered solely a wear and tear disease but our understanding of OA is changing.

A common explanation for its appearance is that you’ve overused the joint. The 50% prevalence of OA in older populations seems to support this assessment.

More recently however researchers have suggested inflammation may play a major role. Either in the joint itself, or more broadly in the body as a whole.

Studies have shown that reducing systemic inflammation can slow the progression of the disease and reduce symptoms.

Exercise and Osteoarthritis

You’ve probably been told exercise will benefit you. Perhaps you’re not sure where to start though, or you’ve had mixed results applying it.

As OA is often described as a wear and tear disease, you might also be wondering if more wearing and tearing will help.

Fair point.

Rest assured most studies show exercise will help. Ideally activity should take place within the current physiological limits of the joint however.

What does that mean? Don’t do too much too soon.

So what’s the best exercise for knee Osteoarthritis?

To answer this question, let’s look at both the risk factors for developing OA and the consequences of the disease.

Exercise which is designed with these factors in mind is more likely to be successful.

Muscle weakness and Osteoarthritis

Whether muscle weakness is a consequence of OA, or a factor in its development is open to debate. From our perspective it doesn’t really matter.

Getting weak muscles stronger seems to help.

Most of the research in this area has been carried out on the knee. There are some studies on hip OA, but little on hand and wrist presentations of the disease. If you suffer with OA at other joints, you can extrapolate what seems to work at one joint to another.

Unsurprisingly strength training has been shown to be the most successful intervention for getting weak muscles stronger. It’s also been shown to reduce pain and improve function.

Applying this type of training with care is the key to avoiding negative consequences such as increased soreness and inflammation.

Providing the exercise takes place within the control of your muscular system and the load is progressed sensibly, the risks are mitigated.

It’s also useful to know that many of the benefits of strength training can be achieved without using heavy weights. Studies that have compared high intensity resistance training to training at more moderate loads have shown similar results.

Joint forces and Osteoarthritis

The focus of any OA exercise programme should be to stimulate positive adaptation in the body, without exposing the problematic joints to unnecessary amounts of force.

Because force is invisible and everyone’s tolerance is different, this can be difficult to judge.

For example, you might have been told to avoid running due to the relatively high forces involved. This may be sensible depending on what stage your OA is at and your exercise history.

Few would think that golf exposes the knee to larger amounts of force however.

Again this may not be a problem but it’s sensible to listen to your joints. If you experience regular flare ups from a particular activity, make adjustments. You can reduce variables such as time and intensity to see if that helps.

This is especially important if you’re trying to delay joint replacement surgery as long as possible.

My bias is to first strengthen the muscular system in a controlled environment using resistance training. This enables me to control the forces at the joints, whilst having the maximum effect on the muscular system.

You may find adopting this approach will ultimately enable you to participate in more of the activities you enjoy. All without causing negative reactions at the joint.

Biomechanics and Osteoarthritis

How you move has been shown to influence OA progression.

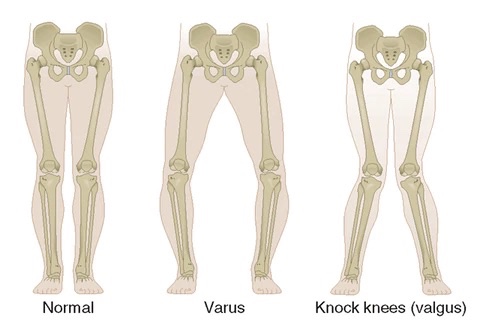

Individuals whose knees tend towards a varus position, are more likely to show greater OA progression in the medial compartment of their knees.

Whereas people who have more of a valgus knee alignment, are more likely to experience issues in the lateral compartment of their knees.

How force is distributed through your knees is influenced by both the muscles of your ankle and your hip.

Training both of these areas may help alter these forces. Studies have shown hip muscle strengthening can both reduce pain and improve function in people with knee OA.

Body fat and inflammation and their role in Osteoarthritis

It’s well established that excess body fat accelerates the progress of knee OA. This was thought to be due to the additional load placed through the knees as a result.

Whilst load may still be a factor, it’s interesting to note there’s also a connection between obesity and OA of the hand. An area of the body that’s not exposed to weight bearing.

This points to the role systemic inflammation may play in the progress of OA and why losing body fat should be a priority.

Summary

Osteoarthritis (OA) affects the whole joint, not just cartilage, and is influenced by chronic inflammation.

Exercise is highly beneficial, with resistance training shown to be the most effective for reducing pain, improving function, and strengthening weak muscles.

Managing joint forces is key—choose activities carefully and adjust if flare-ups occur.

Strengthening surrounding muscles, especially at the hip and ankle, can improve biomechanics and slow OA progression.

Reducing body fat further helps by lowering systemic inflammation.

Together, strength training, smart activity choices, and weight management form the foundation for managing knee OA.