In this post we discuss if taking 10,000 steps a day is necessary for our health and why it might actually be harmful in some cases.

Everybody likes a number to aim for when they’re exercising. Common sense will tell you that number can’t be the same for everybody.

Despite this, every now and again the marketers get into our heads and a seemingly random goal becomes a ubiquitous one. This is certainly the case for the 10,000 steps a day target.

History and evidence for 10,000 steps

The history of the 10,000 steps recommendation can be traced back to a pedometer that was made following the Tokyo Olympics in 1964. Roughly translated the name of the product was ‘the 10,000 steps meter’ and so a goal was born from a name.

As with much in the fitness world, the product or claim becomes popular and then the science takes place afterwards.

There’s little evidence to suggest that taking 10,000 steps a day will do much more for you than taking 7,500 steps day. And taking 7,500 steps a day doesn’t provide that much more benefit than taking 5000 steps a day.

Additionally the single metric by which these numbers are compared is early death. Is this the best marker of optimal health? I would argue not.

My grandmother lived into her 90s. The last years of her life were spent bed ridden and in chronic pain however.

It seems with these types of targets we are valuing longevity over structural integrity.

Osteoarthritis and 10,000 steps a day

One of the key markers for healthy ageing is the absence of chronic pain. Whilst this is a multi-factorial issue, the most common cause is osteoarthritis (OA).

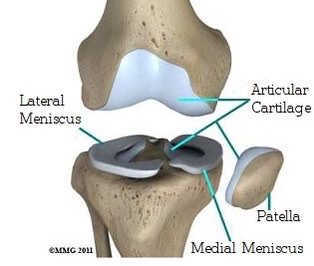

OA is characterised by the degeneration of the cartilage which covers the ends of bones and enables the smooth function of the joints involved.

The most common joint affected is the knee followed by the hip and the joints of the hand. You’ll notice these joints are among the most used.

Cartilage is an interesting material because although it benefits from a certain level of exercise, past a point it begins to degrade.

Whilst bone, muscle, tendons and ligaments can heal, cartilage can not. Once you pass the tipping point the damage may be permanent.

Risk factors for Osteoarthritis

There are certain risk factors for developing OA, one of which is previous injury to a joint. Another is excessive loading. Of course what constitutes excessive loading for one person may be completely different from another.

Studies in runners for example have shown variable results. A certain amount of running has been shown to be protective against OA in some studies. Whilst others involving former elite level athletes have found a greater incidence of OA.

There are a myriad of factors involved including who you picked for your parents, your biomechanics and the status of your health.

This makes it difficult to predict who will develop OA and who won’t.

What we do know however is that if you’ve already experienced issues in a joint, you’re more likely to develop OA. And that if you load that joint excessively, you may make matters worse.

So if your goal is to achieve 10,000 steps a day regardless of any pain you might be experiencing at a joint, is this of benefit to your health? The evidence would say probably not.

Summary

Given the finite nature of joint cartilage it’s better to apply caution if you experience pain from a joint.

Don’t continue to exercise if it causes you pain, especially if you’re chasing an arbitrary target that may not be that beneficial to your health in the long run anyway.

Many of the risk factors for OA can be altered. Improving how you move, getting stronger and reducing chronic inflammation can all have a positive effect. Focus on these first.